Dear Diary,

Dear Diary,Judge Says 'Intelligent Design' Is Not Science

He calls a school board's effort to teach it as an alternative to evolution unconstitutional.

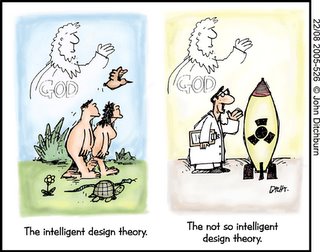

A federal judge, saying "intelligent design" is "an interesting theological argument, but … not science," ruled Tuesday that a school board violated the Constitution by compelling biology teachers to present the concept as an alternative to evolution.

The ruling came after U.S. District Judge John E. Jones III heard 21 days of testimony in a closely watched trial that pitted a group of parents against the school board in the town of Dover, Pa. In October 2004, the board had required school officials to read a statement to ninth-graders declaring that Charles Darwin's ideas on evolution were "a theory … not a fact," and that "gaps in the theory exist for which there is no evidence."

"Intelligent design is an explanation of the origin of life that differs from Darwin's view," the statement said.

Jones, a church-going conservative who was appointed to the federal bench by President Bush in 2002, said the statement was clearly designed to insert religious teachings into the classroom. He used much of his 139-page ruling to dissect arguments made for intelligent design.

Legal experts described the ruling as a sharp defeat for the intelligent design movement — one likely to have considerable influence with other judges, although it is only legally binding in one area of Pennsylvania.

The "overwhelming evidence" has established that intelligent design "is a religious view, a mere relabeling of creationism, and not a scientific theory," Jones wrote. Public remarks by school board members, he said, made clear that they adopted the statement to advance specific religious views. Testimony at the trial included remarks from a board meeting, where one of the backers of the intelligent design statement "said words to the effect of '2,000 years ago someone died on a cross. Can't someone take a stand for him?' " the judge noted.

Supporters of intelligent design argue that biological systems are so complex that they could not have arisen by a series of random changes. The complexity of life implies an intelligent designer, they say. Most of the movement's spokesmen take care not to publicly say whether the designer they have in mind is equivalent to the God in the Bible. On that basis, they argue that their concept is scientific, not religious.

But Jones said the concept was inescapably religious."Although proponents of the [intelligent design movement] occasionally suggest that the designer could be a space alien or a time-traveling cell biologist, no serious alternative to God as the designer has been proposed by members" of the movement, including expert witnesses who testified, Jones wrote.

Remarks by board members that they had secular purposes in mind — to improve science teaching and to foster an open debate — were a "sham" and a "pretext for the board's real purpose, which was to promote religion in the public school classroom," he wrote.

Anticipating attacks, Jones said his ruling was not the "product of an activist judge."He said school board officials had lied in their testimony and excoriated them for not bothering to understand what intelligent design was about before making their decision.

He rebuked what he called the "breathtaking inanity of the board's decision."

"This case came to us as the result of the activism of an ill-informed faction on a school board, aided by a national public interest law firm eager to find a constitutional test case" on intelligent design, he wrote.

The school district will not appeal the ruling, said Patricia Dapp, who was elected to the Dover board this year. The supporters of intelligent design have been voted out of office, and eight members of the board now oppose the concept, she said. The Dover trial, in which Jones heard testimony from leading advocates of intelligent design as well as experts on evolutionary theory, was one of several battlegrounds for intelligent design in the last year.

In January, a U.S. district judge in Georgia ruled that the school system in Cobb County, near Atlanta, had violated the Constitution by requiring stickers to be placed on biology textbooks casting doubt on the theory of evolution.This month, a federal appeals court in Atlanta considered arguments in the case, with at least one judge expressing doubts about the lower court ruling.

In Kansas, the state Board of Education has changed the definition of science to permit supernatural explanations.That reliance on the supernatural was key to Jones' rejection of the Dover school board's position.Intelligent design arguments "may be true, a proposition on which this court takes no position," he wrote, but it "is not science." "The centuries-old ground rules of science" make clear that a scientific theory must rely solely on natural explanations that can be tested, he wrote. That portion of the decision won praise from Kenneth R. Miller, a biology professor at Brown University in Providence, R.I. He was the lead expert witness for the parents in the case and is the author of biology textbooks used in college and high school classrooms. Miller testified that it was crucial that scientific propositions be able to be tested. To illustrate his point, Miller, an avid fan of the Boston Red Sox, testified that when his team beat the New York Yankees in the 2004 baseball playoffs, a fan might have believed "God was tired of [Yankee owner] George Steinbrenner and wanted to see the Red Sox win." "In my part of the country, you'd be surprised how many people think that's a perfectly reasonable explanation for what happened last year. And you know what? It might be true. But it certainly is not science … and it's certainly not something we can test," Miller said.

Supporters of intelligent design denounced Jones' ruling along the lines the judge had predicted."The Dover decision is an attempt by an activist federal judge to stop the spread of a scientific idea … and it won't work," said John West, associate director of the Center for Science and Culture at the Discovery Institute. The institute, based in Seattle, is a major backer of the intelligent design movement."Anyone who thinks a court ruling is going to kill off interest in intelligent design is living in another world," West said.Richard Thompson of the Thomas More Law Center, the lead lawyer for the school board members, called the ruling an "ad hominem attack on scientists who happen to believe in God.""The founders of this country would be astonished at the thought that this simple curriculum change [was] in violation of the Constitution that they drafted," he said.

But Lee Strang, a constitutional law professor at Ave Maria School of Law in Ann Arbor, Mich., which advocates a greater role for religion in public life, said that given Supreme Court precedents and the evidence that Dover school board members had religious goals in mind, Jones' ruling was inevitable.The Supreme Court in 1987 barred the teaching in public schools of what backers called creation science. The concept of intelligent design emerged after that ruling, Jones noted in his ruling.

Douglas Laycock of the University of Texas School of Law said the ruling would probably have considerable influence because it came after a trial in which "both sides brought in their top guns" to testify. The judge's detailed ruling "will be quite persuasive to other judges and lawyers thinking about provoking a similar case elsewhere," he said.

Marci Hamilton, a professor at Cardozo School of Law in New York, who is an expert on religious freedom issues, agreed that the ruling could have broad ramifications."These are tough times to rule against a religious group," Hamilton said. "This decision sends a message to judges that it is not anti-religious to find things like intelligent design unconstitutional."

Eric Rothschild, one of the plaintiffs' lawyers, called the ruling "a real vindication of the courage [the parents] showed and the position they took."The testimony, he said, had demonstrated that "the emperor had no clothes. The judge concluded that intelligent design had no scientific merit" and could not "uncouple itself from religion."