Dear Diary,

according to some IT is.

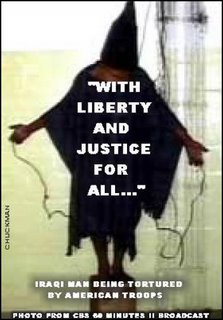

"The Truth about Torture It's time to be honest about doing terrible things. "

by Charles Krauthammer 12/05/2005

DURING THE LAST FEW WEEKS in Washington the pieties about torture have lain so thick in the air that it has been impossible to have a reasoned discussion. The McCain amendment that would ban "cruel, inhuman, or degrading" treatment of any prisoner by any agent of the United States sailed through the Senate by a vote of 90-9. The Washington establishment remains stunned that nine such retrograde, morally inert persons--let alone senators--could be found in this noble capital.

Now, John McCain has great moral authority on this issue, having heroically borne torture at the hands of the North Vietnamese. McCain has made fine arguments in defense of his position. And McCain is acting out of the deep and honorable conviction that what he is proposing is not only right but is in the best interest of the United States. His position deserves respect. But that does not mean, as seems to be the assumption in Washington today, that a critical analysis of his "no torture, ever" policy is beyond the pale.

Let's begin with a few analytic distinctions. For the purpose of torture and prisoner maltreatment, there are three kinds of war prisoners:

First, there is the ordinary soldier caught on the field of battle. There is no question that he is entitled to humane treatment. Indeed, we have no right to disturb a hair on his head. His detention has but a single purpose: to keep him hors de combat. The proof of that proposition is that if there were a better way to keep him off the battlefield that did not require his detention, we would let him go. Indeed, during one year of the Civil War, the two sides did try an alternative. They mutually "paroled" captured enemy soldiers, i.e., released them to return home on the pledge that they would not take up arms again. (The experiment failed for a foreseeable reason: cheating. Grant found that some paroled Confederates had reenlisted.)

Because the only purpose of detention in these circumstances is to prevent the prisoner from becoming a combatant again, he is entitled to all the protections and dignity of an ordinary domestic prisoner--indeed, more privileges, because, unlike the domestic prisoner, he has committed no crime. He merely had the misfortune to enlist on the other side of a legitimate war. He is therefore entitled to many of the privileges enjoyed by an ordinary citizen--the right to send correspondence, to engage in athletic activity and intellectual pursuits, to receive allowances from relatives--except, of course, for the freedom to leave the prison.

Second, there is the captured terrorist. A terrorist is by profession, indeed by definition, an unlawful combatant: He lives outside the laws of war because he does not wear a uniform, he hides among civilians, and he deliberately targets innocents. He is entitled to no protections whatsoever. People seem to think that the postwar Geneva Conventions were written only to protect detainees. In fact, their deeper purpose was to provide a deterrent to the kind of barbaric treatment of civilians that had become so horribly apparent during the first half of the 20th century, and in particular, during the Second World War. The idea was to deter the abuse of civilians by promising combatants who treated noncombatants well that they themselves would be treated according to a code of dignity if captured--and, crucially, that they would be denied the protections of that code if they broke the laws of war and abused civilians themselves.

Breaking the laws of war and abusing civilians are what, to understate the matter vastly, terrorists do for a living. They are entitled, therefore, to nothing. Anyone who blows up a car bomb in a market deserves to spend the rest of his life roasting on a spit over an open fire. But we don't do that because we do not descend to the level of our enemy. We don't do that because, unlike him, we are civilized. Even though terrorists are entitled to no humane treatment, we give it to them because it is in our nature as a moral and humane people. And when on rare occasions we fail to do that, as has occurred in several of the fronts of the war on terror, we are duly disgraced.

The norm, however, is how the majority of prisoners at Guantanamo have been treated. We give them three meals a day, superior medical care, and provision to pray five times a day. Our scrupulousness extends even to providing them with their own Korans, which is the only reason alleged abuses of the Koran at Guantanamo ever became an issue. That we should have provided those who kill innocents in the name of Islam with precisely the document that inspires their barbarism is a sign of the absurd lengths to which we often go in extending undeserved humanity to terrorist prisoners.

Third, there is the terrorist with information. Here the issue of torture gets complicated and the easy pieties don't so easily apply. Let's take the textbook case. Ethics 101: A terrorist has planted a nuclear bomb in New York City. It will go off in one hour. A million people will die. You capture the terrorist. He knows where it is. He's not talking.

Question: If you have the slightest belief that hanging this man by his thumbs will get you the information to save a million people, are you permitted to do it?

Now, on most issues regarding torture, I confess tentativeness and uncertainty. But on this issue, there can be no uncertainty: Not only is it permissible to hang this miscreant by his thumbs. It is a moral duty.

Yes, you say, but that's an extreme and very hypothetical case. Well, not as hypothetical as you think. Sure, the (nuclear) scale is hypothetical, but in the age of the car-and suicide-bomber, terrorists are often captured who have just set a car bomb to go off or sent a suicide bomber out to a coffee shop, and you only have minutes to find out where the attack is to take place. This "hypothetical" is common enough that the Israelis have a term for precisely that situation: the ticking time bomb problem.

And even if the example I gave were entirely hypothetical, the conclusion--yes, in this case even torture is permissible--is telling because it establishes the principle: Torture is not always impermissible. However rare the cases, there are circumstances in which, by any rational moral calculus, torture not only would be permissible but would be required (to acquire life-saving information). And once you've established the principle, to paraphrase George Bernard Shaw, all that's left to haggle about is the price. In the case of torture, that means that the argument is not whether torture is ever permissible, but when--i.e., under what obviously stringent circumstances: how big, how imminent, how preventable the ticking time bomb.

That is why the McCain amendment, which by mandating "torture never" refuses even to recognize the legitimacy of any moral calculus, cannot be right. There must be exceptions. The real argument should be over what constitutes a legitimate exception. Click here for the remainder of this article http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/006/400rhqav.asp

*

*

Amnesty seeks UK probe into CIA flights

http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/F70C4486-A501-4F69-9695-59F92AEB8226.htm

Amnesty International says Britain allowed the CIA to operate flights on its territory to transport terrorism detainees illegally and demanded that the government launch an investigation.

"The UK has allowed these aircraft to land, re-fuel and take off from their territory," the human rights group's regional director Claudio Cordone said in a statement on Thursday.

"The UK government must launch an immediate, thorough and independent investigation into mounting evidence that its territory has been used to assist in unlawfully transporting detainees to countries where they may face "disappearance", torture or other ill-treatment," he added.

The British government said on Monday it had no evidence that the current US administration had been transporting terrorism suspects through British airports.

Cordone said: "Whether the US is sending people to other countries to be tortured, or snatching them in other countries to be abused in Guantanamo, international law prohibits the UK, or any other state, from aiding or abetting them."

CIA prisons

Human rights groups accuse the CIA of running secret prisons in eastern Europe and covertly transporting detainees -a practice known as "extraordinary rendition". They say incommunicado detention often leads to torture.

"The UK government must launch an immediate investigation into mounting evidence that its territory has been used to assist in unlawfully transporting detainees"Amnesty International statementThe Amnesty statement named several men it said had been abducted by the CIA and flown to Jordan and Egypt as part of the US campaign of "extraordinary rendition".

In each case a Gulfstream V, registration N379P, had stopped to refuel at Prestwick airport in Scotland on its way back to the United States after dropping off its passengers, it said. It cited the case of Jamil Qasim Saeed Mohammed who it said was seen being bundled aboard the CIA plane by masked men in Karachi on 23 October, 2001. The plane then flew to Jordan and the following day, now without its passenger, it flew to Prestwick and then on to Dulles International airport near Washington.

Amnesty demanded that the United States reveal Mohammed's whereabouts. UK stop-overAmnesty said that on 12 January, 2002, Indonesian security officials saw Muhammad Saad Iqbal Madni being put on the plane in Jakarta and flown to Cairo. Once again the plane stopped in Prestwick to refuel after depositing its passenger.

It said Iqbal Madni had since been returned to US jurisdiction and was now a detainee in Guantanamo Bay where fellow detainees had said he was on the verge of a breakdown.

Amnesty cited a third case where a Swedish investigation has already revealed that US security officials took Ahmed Agiza and Mohammed al-Zari from Sweden to Cairo for torture.

In total, Gulfstream N379P had been logged between 2001 and 2005 making at least 78 stopovers at British airports while en route to or from destinations such as Baku, Dubai, Cyprus, Karachi, Qatar, Riyadh, Tashkent, and Warsaw, Amnesty said.